At dawn, as a girl, I woke to the sound of the early morning flights from the nearby Miami airport roaring overhead. It soon became a background noise. In the school year 1951-1952, I started first grade at Miami Springs Elementary. As a child I was unaware of the women struggling to earn a living wage as flight attendants. I was unaware of those women and the unions they built.

My own right to work until retirement was secured by their decades-long efforts. Many women were denied job security for a job well-done, and were forced to “retire” at 32 or 35. Many did not have the opportunity to retire with benefits. I salute their persistent efforts to be treated with respect as valuable employees. Remember, the risk of death while working as a flight attendant in the earlier years was real. “In the 1950s and 1960s US airlines experienced at least six crashes each year – most of which lead to the deaths of all on board. This shocking statistic began dropping dramatically from the late 1970s, and such crashes are very rare now.”1

I feel a strong affinity to these determined women since I also sought to eliminate sex discrimination when I worked for TWA from 1969 to 1985. I continue to benefit from their concerted efforts. Today I’m writing about their challenges in the 1950s and about the shift at TWA to new uniforms after eleven years in the “cut-out” style of uniform.

One stewardess involved in union organizing in the 1940s observed, “The airline hires us young, works us hard, and then wants us gone.” This strategy intensified in the 1950s although one accomplishment by flight attendants in 1952 is worthy of note.

1951

Flight attendants were facing an on-the-job “speedup” in 1951! The introduction of the Super-G Constellation, or Model 1049, doubled their workload. “This stretched variant of the earlier Constellation boasted unheard-of refinements, such as air conditioning, reclining seats, and extra lavatories. It was a plane ahead of its time, at least twice as fuel efficient as the industry’s first jets and as efficient as many of today’s modern aircraft.2

The flight attendants working on the faster aircraft were facing shorter flying times and more passengers for the same scheduled in-flight services (and the same low pay). These working women were the first to experience jetlag and to describe the effects! Not surprisingly their experiences of flight-related fatigue were not taken seriously.

How many steps did a working flight attendant take on a single flight? On a routine flight from Chicago to Miami in 1948, the flight attendant walked an exhausting eight miles as measured by the pedometer she wore that day. The airlines did not introduce serving carts until the late 1950s. Imagine this scenario: one to three hostesses using the cramped galley “as a base for preparing, serving, and clearing multi-course meals and drinks for planeloads approaching one hundred passengers.” 3

1952

Finally, in 1952 the Civil Air Administration officially required the presence of flight attendants on commercial aircraft where their “duties would include but are not necessarily limited to cabin-safety-related responsibilities.”4 The efforts to obtain certification as trained safety professionals on board commercial aircraft has been denied (in part due to the opposition of the pilots union) to flight attendants for the last seventy-five years.5

1953

From the earliest years, if a flight attendants married, she was dismissed or, if she was lucky, she might be offered a ground position. Yet, some women enjoyed the airborne work, enjoyed supporting themselves and reveled in the chance to travel on their own. Respected historian Kathleen M. Barry described the situation:

“As the flight attendant workforce had steadily expanded since the 1930s, so had the numbers of women who had stayed in the job for several years, even while the average tenure remained at two or three years. Some veterans took the few routes of mobility available to female flight attendants, becoming stewardess supervisors or trainers, but most continued to serve passengers. Airlines minimized veteran male and female flight attendants’ claims to economic rewards for time served by capping salary increases at eight to ten years and by not offering pension plans or other long-term benefits. But veteran stewardesses, even if relatively economical as long-term workers, still left airlines with the ‘problem’ of employing maturing women in what was supposed to be a temporary sojourn between school and marriage.

American Airlines pioneered the ‘solution’ by declaring that as of December 1953, it would ground stewardesses upon their thirty-second birthday. American’s official rational for the new policy was ‘based on the established qualifications for Stewardesses, which are attractive appearance, pleasant dispositions, even temperament, neatness, unmarried status, and the ability and desire to meet and serve passengers. Basic among the qualifications is an attractive appearance. Such an appearance ordinarily is found to a higher degree in a younger woman. Therefore the establishment of an age limit will best effectuate and preserve the concept of Stewardess service as it is understood by this Company.’6

American imposed the age ceiling as a precondition of employment. New stewardesses signed a pledge to resign ‘voluntarily’ at thirty-two.”7

Stewardesses Not Entitled to Job Security

Eliminating sex discrimination in employment practices was one of the efforts the flight attendant unions attempted since first organizing in the late 1940s. Using the tools of collective bargaining and of the grievance procedures brought limited success. In this drastic situation in 1953 “the Air Line Stewardesses and Stewards Association (ALSSA) forced a limited compromise. ALSSA managed to restrict the age limit to new hires. The union immediately saved the jobs of sixty-four American stewardesses then already thirty-two or older and set a precedent of so-called ‘grandmother rights’. ‘Grandmother rights’ not only protected veteran stewardesses jobs at American and other carriers. They ensured that a few more mature stewardesses would remain in the job as living evidence of how arbitrary the age ceilings were….”8

At TWA about 10% of the women benefited from this “grandmother” exemption because they were hired before this policy went into effect! But, Barry points out that “the rare job security ‘grandmothered’ stewardesses enjoyed came at the cost of being the unwelcome exception to airlines’ increasingly stringent demands for youthfulness.” With these policies, I believe the airlines also sought compliant employees unwilling to question unfair working conditions. As the astute union woman in the 1940s said, “The airline hires us young, works us hard, and then wants us gone.”

Despite years of activism and lawsuits it was not until the mid 1960s that the flight attendants were successful in forcing the airlines to eliminate the age and marriage restrictions as conditions of employment. I’ll write more about that struggle and the win at a later date.

1955

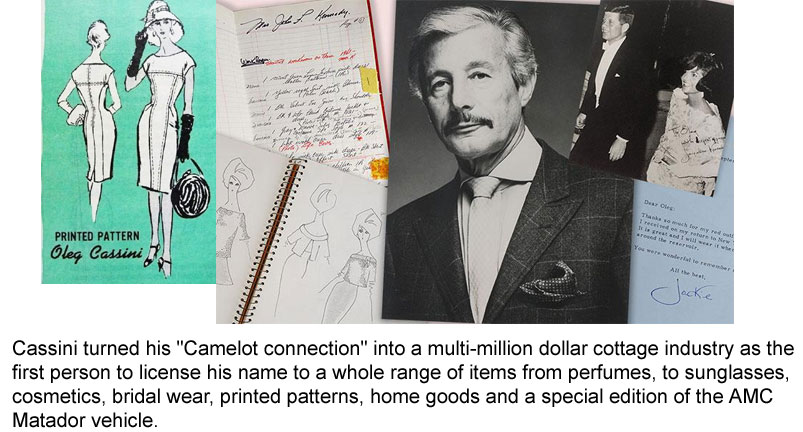

Howard Hughes, with his Hollywood connections, was still at the helm of TWA in the mid 1950s when Hollywood designer Oleg Cassini was selected to design the new TWA hostess uniforms. Cassini had worked as a designer first for Paramount Pictures and later (1942) for Twentieth Century Fox. His assignment to replace the unique “cutout-design” uniform that had symbolized TWA for a record eleven years was a challenge.

Cassini designed a variation on that cut-out design. The collarless jacket of the fitted suit emphasized the red TWA lettering on the right shoulder. The hip length jacket with five covered buttons was long-sleeved in both the summer and winter uniforms. The winter uniforms were a medium brown wool. The more appealing summer version in green lightweight wool featured the same collarless jacket. The straight-fitting skirt with a rear pleat fell below the knees.

For decades wool has been used extensively in year-round suits for women and for men because wool resists abrasion, drapes well and wrinkles little. Both winter and summer uniforms were worn with a white cotton blous-slip. Either brown pumps or brown and white spectator pumps as well as white gloves completed the uniform.

Details: The red embroidered TWA letters appeared on the right front of the blouse too. The blouse had front button fastenings. The white blouse-slip was cotton on the blouse section and nylon on the lower slip section. The sturdy brown or green wool hat featured a left upsweep to the crown which was accented with a three color cockade, that is, an ornamental knot of ribbons. The hostess half wing was pinned to the center of the ribbon cockade. The uniform was manufactured by Briny Marlin and the hat made by Mae Hanauer.

Most sources indicate that the colors of these uniforms were coordinated with the cabin interiors of TWA’s Lockheed Constellation for the innovative trans-Atlantic service at the height of the propliner era. See for yourself. Return to the the third group of photos (above) with the interior view of the Super-G Constellation. These uniforms were worn by the TWA hostesses until 1960. Years later, in 1963, Oleg Cassini became First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s official designer.

Stereotypes of the stewardess of earlier decades continue to flourish. Occasionally I see a tribute as appreciative as this: “Stewardesses were globe-trotting modern women who always looked professional, capable, and enthused.”10

In many ways wearing a uniform is a costume for a role devised by an employer. Wearing a classic fitted suit with hat and now, for the first time, white gloves, is rather like a stage appearance. Both inside the airport terminal and then on the airplane itself these women were trained safety professionals, capable of evacuating an aircraft in 90 seconds and enthusiastic about a career in aviation. The uniform added to their dignity. The women who worked as flight attendants, whether called hostess or stewardess, had carved out a niche in aviation for women in a time when women had limited career choices. Yet, nostalgia, the sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, dominates most descriptions of aviation’s yesteryear–especially commentary about the stewardess.

Notes

1 https://www.express.co.uk/travel/articles/1055852/flights-united-airlines-cabin-crew-lax-air-hostess-turbulence

2 from https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/news/features/history/constellation.html

3 Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants, Kathleen M. Barry, p. 45 https://books.google.com/books/about/Femininity_in_Flight.html?id=fGVy_CsvIwgC

4 https://www.afacwa.org/milestones

5 Femininity in Flight, p.73

6 Femininity in Flight, p.112

7 Femininity in Flight, p.124

8 Femininity in Flight, p.113

9 https://www.crfashionbook.com/fashion/g32227361/flight-attendant-fashion-dior-yves-saint-laurent/?slide=2

10 https://www.southernliving.com/fashion-beauty/vintage-flight-attendant-uniform