As a woman passionate about the liberation of women, I’m weaving several threads through my story telling. I’ve recently been writing about my own family, but before leaving the 1940s time frame, I’m writing about women who paved the way for me to work as a flight attendant. I want you to know the United Airlines stewardesses who started the first stewardess union.

In 1945 (my birth year) United Airlines stewardesses were paid the same $125 a month as the initial group of “sky girls” in 1930! Determined and single-minded women began organizing, first at United. One union activist said, “We had no rights, let’s put it that way. We were at the mercy of the company. There were no rules or regulations about monthly flight time. If a stewardess didn’t show up to replace you on multi-stops across the country, the company would just say, ‘You have to continue flying.'” 1

In late 1944 United’s chief stewardess, Ada J. Brown, frustrated by the company’s unwillingness to upgrade conditions for the stewardesses, left her management position to return to the all-female rank and file and to begin organizing a union. She recalled, “As chief stewardess I tried to get improvements for the girls with salary, flight regulations, and protection from unjust firing.”2

Other United stewardesses including Sally Thometz, Frances Hall, Edith Lauterbach and Sally Watt became enthusiastic union organizers–organizing at the bases in San Francisco, Denver, and Chicago.

“I had planned to fly one year and quit,” Lauterbach told an interviewer in 1985. “It was a male-dominated industry and they weren’t anxious to have women hang around.” Later she added, “After we flew for a while, we realized it wasn’t as glamorous as we thought. We had to crawl on our hands and knees during rough weather and deliver meals in the turbulence, clean up after the passengers when they got sick…. Those little planes were all over the sky in bad weather.”3

By August 1945 they had organized the Air Line Stewardess Association (ALSA) and began contract negotiations with United. A year later, in April 1946, the women at ALSA had won a contract raising monthly salaries to $155, won a limit of 85 in-flight hours per month, and initiated pay for all the hours spent working on the ground, not just in-flight hours.

By contract, the company agreed to pay for half the initial cost of the uniforms and finally agreed to a grievance procedure to challenge disciplinary actions and dismissals. All these were vitally important work rule improvements for the working women at United. Note: in 1947 ALSA President Ada Brown, 30, marries and becomes a victim of United’s no-marriage rule. She is forced to retire from her career and the union presidency.4

In the generally well-paid airline industry, flight attendants were at the bottom of the wage ladder. By 1955 the average salary for flight attendants in the U.S. was just under $3,300, while pilots and co-pilots claimed more than three times as much. Other airline ground workers such as maintenance, clerical, etc. took home average yearly pay of between $4,300 and $5,300.5

The successful bargaining at United changed the picture at every airline! Within five years two-thirds of U.S. stewardesses at sixteen air lines had union representation. Ada J. Brown is an admired heroine for me!

Update: I just this morning discovered a youtube video featuring interviews with both Ada Brown and Edith Lauterbach! Lauterbach retired from United in 1989. She continues to be involved in union work with AFA! Produced by the current flight attendant union, the Association of Flight Attendants (AFA), the film begins with historical footage. Current coverage includes discussion of the vital role of flight attendants during the 9/11 attacks and introduces flight attendants as aviation’s “first responders”. View this 18 minute video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1111&v=qKbn905qohI&feature=emb_logo

All these gutsy women left a lasting legacy to women workers and to flight attendants. Before flying for United, Edith Lauterbach (mentioned above) had earned a degree in political science from UC Berkeley in 1942, and later said she joined United as “a lark.” I, too, had earned a degree in political science (1967). Like Edith, it did not take me long to become a union activist.6

Let’s talk about uniforms since the subject was important in that first union contract. When I started with TWA in 1969, we were told we had to pay for our first set of uniforms. Should the company change our uniforms, they would then pay for the replacements. We paid for three outfits for summer and three for winter. TWA took payments out of our meager paychecks. This is quite a corporate trick—get your employees to cover the company’s uniform costs!

This was a good deal for the airlines for the many decades stewardess careers were short due to the restrictive age and no-marriage rules of the airlines. Age requirements drove down wages and prevented career-oriented stewardesses from accruing seniority or benefits. These regulations also aimed to prevent stewardesses from organizing for better pay and work policies. Once we legally challenged those rules, flight attendants had longer flying careers. One result of those changes meant that the airline companies would have to absorb a larger percentage the cost of their employees’ uniforms.

Uniforms serve at least two purposes. For those wearing the uniform, you assume that others wearing the same uniform are your colleagues, your allies. For the flying public, the uniform identifies the wearer as representatives of the designated airline. Dressing in a uniform can be a mental shift to accept the responsibilities assigned to you as an employee.

Dressing in a uniform is always full of symbolism. Uniforms are meant to convey messages–both to the wearer and to the observer. “Symbols have both psychological and political effects, because they create the inner conditions (deep-seated attitudes and feelings) that lead people to feel comfortable with or to accept social and political arrangements that correspond to the symbol system.”7 Women working as stewardesses in 1945 were ready to challenge the white male dominated airline management, the unions, and the government because they realized that the current “social and political arrangements” kept them at a disadvantage! No one expected a pilot to be weighed before a flight, or checked to see that he wore a girdle under his uniform.

I vividly remember the excitement we felt in 1969 when, as trainees, we realized we had made it through training, and would be wearing our uniforms (with a required girdle) the next day at graduation. That particular uniform, introduced in 1968, was not my favorite—who looks good in lemon yellow, or avocado green or a bright pumpkin color? And, really, the skirts were too short for comfort. Rather, it was the idea of the uniform. It was the idea of being part of this flying sisterhood! The uniform was a symbol of our willingness to act in the best interest of the group, to be a team, should we face an emergency.

Before every takeoff we would arm the emergency exit doors. After landing it was imperative that we disarm those powerful escape slides attached to the door. Often the doors were located in a galley. Should we forget, and the galley service people opened the door from the outside, the powerful surge of that escape slide could injure or kill them. We remembered and we cross-checked for each other.

Our skills, our willingness to take charge in case of an emergency were almost invisible. We were trained to evacuate hundreds of passengers. We were safety directors. We were safety directors disguised as merely helpful crew members. Neither the flying public nor the airlines wanted to remind passengers that flying could be dangerous. Institutional acknowledgment of our capabilities would have been extremely valuable to us as a group and as individuals. Neither government officials nor the airlines wanted that to happen.

Our flight attendant unions have long sought professional certification of basic proficiency for flight attendants by the FAA just as the pilots are certified by the FAA in their area of expertise. For decades the pilots’ union has successfully opposed certification for flight attendants claiming it could compromise their own authority on the aircraft.

Ellen Church, the experienced pilot who United Airlines rejected in 1930, offered United the alternative idea of hiring female nurses to fly as cabin crew. United told her to recruit seven other nurses to fly as “sky girls” on a trial basis. Once that idea was accepted, the women earned their wings and carved out their own niche in aviation. The men in charge handed these women their wing, that is, a half of a set of wings–symbols of their secondary status on board an aircraft. Few women journeyed as regularly or as far from home as these young women who flew as stewardesses. But, they needed to “know their place”.

Few of us questioned our half-wing status until the women’s liberation movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s urged us to rethink all we knew and to question everything!

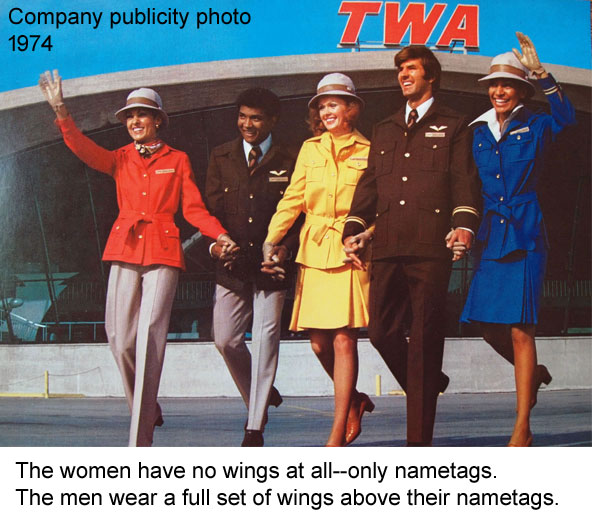

That’s when I really saw my single wing–it was a potent symbol of our secondary status! In fact, when male flight attendants were first hired at TWA in 1974, they received a full set of wings pinned to there uniforms. We wore our single lopsided wing. Of course, most passengers assumed, according to accepted “social and political arrangements”, that these new-hire male flight attendants were our supervisors! The true set of wings the men wore helped reinforce that assumption.

In 1973, as one of the founding members of the feminist organization, Stewardesses for Women’s Rights (SFWR), I helped numerous flying partners file complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. We challenged the restrictions airlines placed on stewardesses’ age, marital status, weight, uniform, grooming regulations, and more. In our list of complaints, we mentioned that disparity in the flight wings awarded to male flight attendants.

Many of our complaints about discrimination were resolved before the EEOC ever heard our cases. The airline industry, under pressure from our flight attendant unions as well as lawsuits, modified most of the list of concerns we had take to the EEOC. Finally, four years later in 1978, when TWA changed uniforms for flight attendants, all of us were wearing the same set of wings. One small, symbolic victory.

Those of us who created Stewardesses for Women’s Rights worked for a variety of airlines and lived all over the U.S. Our purpose in uniting was “to fight sexual and racial discrimination, and to ensure that women are given equal employment and promotional opportunities in the airline industry.” The impact of our efforts as a group pressured our unions to fight for these same goals.

Most of what I see written about flight attendants is inaccurate, or disrespectful or insulting. But Kathleen Barry in Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants has earned my respect. Barry writes that stewardesses “…were quite well aware of what that glamour cost them in conformity to stringent airline rules, in meager wages and no job security, and in working hard at appearing not to be working at all. Given the aura of glamour surrounding postwar stewardesses and all the cultural adulation they received, it may seem surprising that they should also have distinguished themselves by joining the heavily male and blue-color labor movement. But stewardesses’ willingness to to work hard extended not only to embody the airline-defined femininity: it extended to having their efforts taken seriously as real work too.”8

Notes

1 http://yourafa.org/why-afa/weve-come-a-long-way

2 Femininity In Flight: A History of Flight Attendants, Kathleen M. Barry 2007 p.63

3 https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-xpm-2013-feb-06-la-me-edith-lauterbach-20130207-story.html

4 https://unitedafa.org/afa/about/milestones/

5 Femininity In Flight: A History of Flight Attendants, Kathleen M. Barry 2007 p.65

6 https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-xpm-2013-feb-06-la-me-edith-lauterbach-20130207-story.html

7 Carol Christ https://www.goddessariadne.org/why-women-need-the-goddess-part-1

8 Femininity In Flight: A History of Flight Attendants, Kathleen M. Barry 2007 p.58